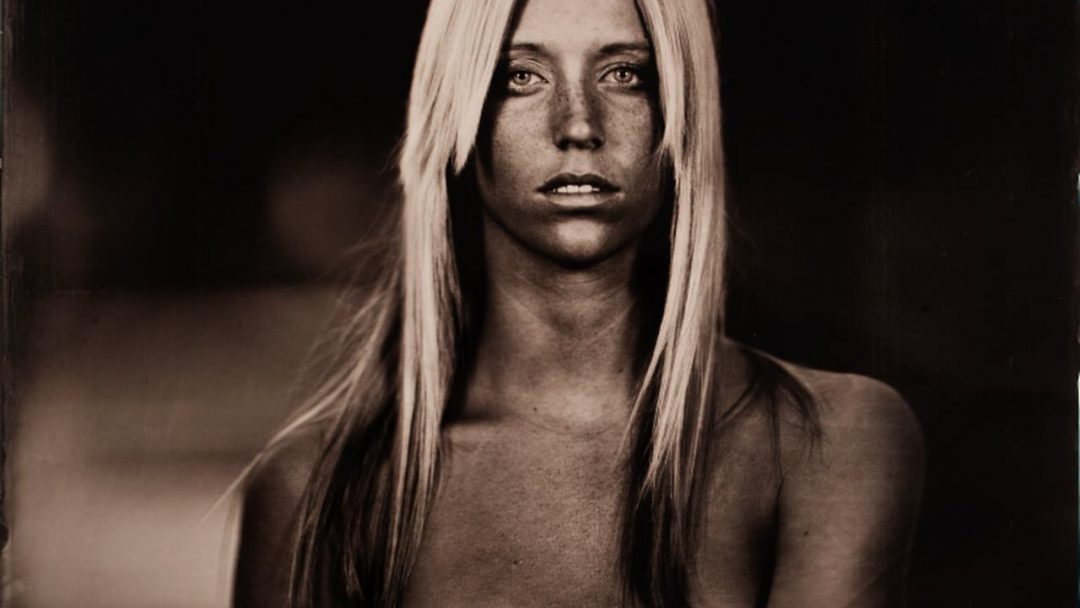

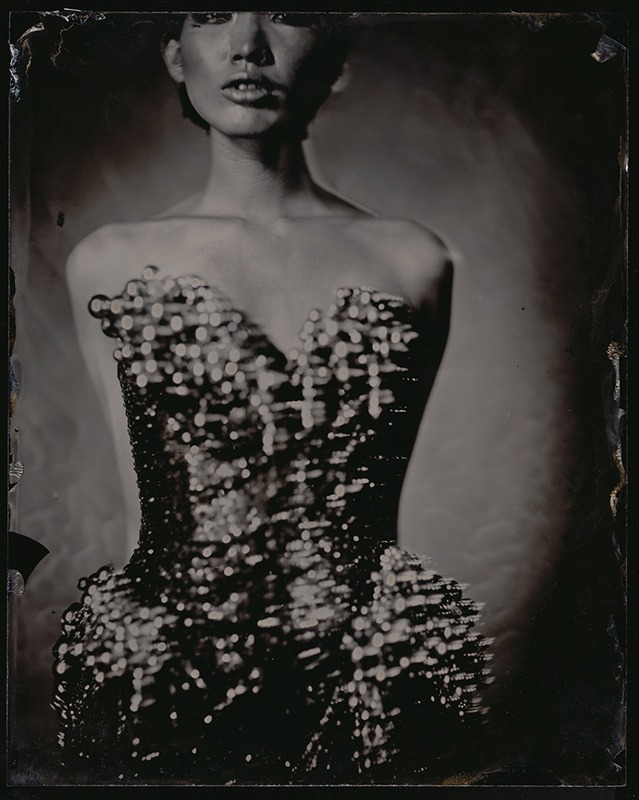

WetPlate – Lost Art Revisited

A video using the real collidion wetplate photography we only dream about in this digital age. Ian Ruhter has forced himself to become a 19th century wet plate master in a 21st century digital, (and some say sad), world.

According to Ruhter, each image costs him $500 to produce and success is spotty at best. The process requires a metal plate to be coated in silver nitrate, then sensitised, exposed, and developed before the wetplate dries.and all done in less than 12-18 minutes.

With a dedicated team, he travels far and wide to complete these one of a kind wetplate landscape and portrait images.

The collodion process is an early photographic process, said to have been invented, almost simultaneously, by Frederick Scott Archer and Gustave Le Gray in about 1851. During the subsequent decades of its popularity, many photographers and experimenters refined or varied the process. By the end of the 1850s it had almost entirely replaced the first practical photographic process, the daguerreotype.

Wetplate?

“Collodion process” is usually taken to be synonymous with the “collodion wetplate process”, an intricate process which required the photographic material to be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed within the span of about fifteen minutes, necessitating a portable darkroom for use in the field. Although collodion was normally used in this wet form, the material could also be used in humid (“preserved”) or dry form, but at the cost of greatly increased exposure time, making these forms unsuitable for the usual work of most professional photographers—portraiture. Their use was therefore confined to landscape photography and other special applications where minutes-long exposure times were tolerable.

During the 1880s the collodion process, in turn, was largely replaced by gelatin dry plates—glass plates with a photographic emulsion of silver halides suspended in gelatin. The dry gelatin emulsion was not only more convenient but could be made much more sensitive, greatly reducing exposure times.

The Tintype

One collodion process, the tintype, was still in limited use for casual portraiture by some itinerant and amusement park photographers as late as the 1930s, and the wetplate collodion process was still in use in the printing industry in the 1960s for line and tone work (mostly printed material involving black type against a white background) as for large work it was much cheaper than gelatin film.

The wet collodion process sometimes gave rise to portable darkrooms, as photographic images needed to be developed while the plate was still wet.

The collodion process produced a negative image on a transparent support (usually glass). This was an improvement over the calotype process, invented by William Henry Fox Talbot, which relied on paper negatives, and the daguerreotype, which produced a one-of-a-kind positive image and could not be replicated. The collodion process, thus combined desirable qualities of the calotype process (enabling the photographer to make a theoretically unlimited number of prints from a single negative) and the daguerreotype (creating a sharpness and clarity that could not be achieved with paper negatives). Collodion printing was typically done on albumen paper.

Daguerreotype vs Collodion

The collodion process had other advantages, especially in comparison with the daguerreotype. It was a relatively inexpensive process. The polishing equipment and fuming equipment needed for the daguerreotype could be dispensed with entirely. The support for the images was glass, which was far less expensive than silver-plated copper, and was more durable than paper negatives. It was also fast for the time, requiring only seconds for exposure.

The wetplate collodion process had a major disadvantage. The entire process, from coating to developing, had to be done before the plate dried. This gave the photographer no more than 15 minutes to complete everything. This made it inconvenient for field use, as it required a portable darkroom. The plate dripped silver nitrate solution, causing stains and troublesome build-ups in the camera and plate holders.

Silver Nitrate

The silver nitrate bath was also a source of problems. It gradually became saturated with alcohol, ether, iodide and bromide salts, dust, and various organic matter. It would lose effectiveness, causing plates to mysteriously fail to produce an image.

As with all preceding photographic processes, the wetplate collodion process was sensitive only to blue light. Warm colours appear dark, cool colours uniformly light. A sky with clouds is impossible to render, as the spectrum of white clouds contains about as much blue as the sky. Lemons and tomatoes appear a shiny black, and a blue and white tablecloth appears plain white. Victorian sitters who in collodion photographs look as if they are in mourning might have been wearing bright yellow or pink.

Despite its disadvantages, wetplate collodion became enormously popular. It was used for portraiture, landscape work, architectural photography and art photography. The world’s largest wetplate collodion glass plate negatives known to survive, measuring 53 inches (1.35 m) x 37 inches (0.94 m), are held at the State Library of New South Wales.

The wetplate process is, in fact, still used by a number of artists and experimenters, who prefer its aesthetic qualities to those of the more modern gelatin silver process. World WetPlate Day is staged annually in May for contemporary practitioners.

Bolton and Sayce

In 1864 W. B. Bolton and B. J. Sayce published an idea for a process that would revolutionize photography. They suggested that sensitive silver salts be formed in a liquid collodion, rather than being precipitated, in-situ, on the surface of a plate. A light-sensitive plate could then be prepared by simply flowing this emulsion across the surface of a glass plate; no silver nitrate bath was required.

Below is an example of the preparation of a collodion emulsion, from the late 19th century. The language has been adapted to be more modern, and the units of measure have been converted to metric.

- 4.9 grams of pyroxylin are dissolved in 81.3 ml of alcohol, 148 ml of ether.

- 13 grams of zinc bromide are dissolved in 29.6 ml of alcohol. Four or five drops of nitric acid are added. This is added to half the collodion made above.

- 21.4 grams of silver nitrate are dissolved in 7.4 ml of water. 29.6 ml of alcohol are added. This is then poured into the other half of the collodion; the brominized collodion dropped in, slowly, while stirring.

The result is an emulsion of silver bromide. It is left to ripen for 10 to 20 hours, until it attains a creamy consistency. It may then be used or washed, as outlined below.

The Wash

To wash, the emulsion is poured into a dish and the solvents are evaporated, until the collodion becomes gelatinous. It is then washed with water, followed by a washing in alcohol. After washing, it is re-dissolved in a mixture of ether and alcohol, and is ready for use.

Emulsions created in this manner could be used wet, but they were often coated on the plate and preserved in similar ways to the dry process.

emulsion plates were developed in an alkaline developer, not unlike those in common use today. An example formula follows.

- A: Pyrogallic acid 96 g Alcohol 1 oz.

- B: Potassium bromide 12 g Distilled Water 30 ml

- C: Ammonium carbonate 80 g Water 30 ml

- When needed for use, mix 0.37 ml of A, 2.72 ml of B and 10.9 ml of C. Flow this over the plate until developed.

The Continuing Alternative

The wetplate collodion process has undergone a revival as an historical technique over the past few decades. There are several practicing ambro typists and tin typists who regularly set up and do images at Civil War re-enactments. Many fine art photographers also use the process and its handcrafted individuality for gallery showings and personal work. There are several makers of reproduction equipment for the contemporary practitioner. The process is taught in workshops around the world and several workbooks and manuals are currently in print.

There are many artists working with wetplate collodion around the globe, including Rob Gibson, Michael Shindler, John Coffer, Kurt Grüng, Jan Sakař, Robyn Hasty, Sally Mann, and Shane Balkowitsch.