Female Pioneers of Photography

I guess unseen can be applied here, but it seems Sothebys’ and others are finally giving these pioneers of photography their due. There were always the females standing in the shadows of males in the photographic world. It wasn’t until the fashion realm made that an oxymoron, with the likes of the Sarah Moons, von Unwerths, Turbevilles, Bettina Rheims, etc., that we saw a change. But these women were not of that era. In fact, there is only one African American female in this list, Carrie Mae Weems, which almost seems to ascribe the title of super hero to her. It was a world that was dominated by the undeniable machismo of maleness. Kind of like a double whammy for the age. But make no mistake,…female pioneers all they were!

At a time when (most) women worried about hairstyles, they jumped into the grimy chemical soup of film photography, never expecting even one iota of recognition for work that many times equaled,… or even surpassed,their male counterparts of that era.

Vivian Maier

Vivian Dorothy Maier was born February 1, 1926, and died on April 21, 2009, in absolute anonymity. And apparently, that was part of her life plan! Maier worked for about forty years as a nanny and persued photography during her spare time. She took more than 150,000 photographs during her lifetime.

Since the accidental discovery of her negatives, many never printed, Maier’s photographs have been exhibited in North America, Europe, Asia and South America. She was constantly taking pictures, many medium format, which she didn’t show anyone.

In 2007, two years before she died, Maier failed to keep up payments on storage space she had rented on Chicago’s North Side. As a result, her negatives, prints, audio recordings, and 8 mm film were auctioned. Three photo collectors bought parts of her work. Not knowing what they had. A man named John Maloof, who had bought most of the negatives, linked his blog to a selection of Maier’s photographs on Flickr, and the results went “viral”, with thousands of people expressing interest.

A Posthumous Discovery

Since her posthumous discovery, Maier’s photographs, and their discovery, have received international attention in mainstream media, and her work has appeared in gallery exhibitions, several books, and two documentary films.

John Maloof has said of her work: “Elderly folk congregating in Chicago’s Old Polish Downtown, garishly dressed dowagers, and the urban African-American experience were all fair game for Maier’s lens.” Photographer Mary Ellen Mark has compared her work to that of Helen Levitt, Robert Frank, Lisette Model, and Diane Arbus. Joel Meyerowitz, also a street photographer, has said that Maier’s work was “suffused with the kind of human understanding, warmth and playfulness that proves she was ‘a real shooter’.”

Maier’s best-known photographs depict street scenes in Chicago and New York during the 1950s and 1960s. A critic in The Independent wrote that “the well-to-do shoppers of Chicago stroll and gossip in all their department-store finery before Maier, but the most arresting subjects are those people on the margins of successful, rich America in the 1950s and 1960s: the kids, the black maids, the bums flaked out on shop stoops.” Most of Maier’s photographs are black and white, and many are casual shots of passers-by caught in transient moments “that nonetheless possess an underlying gravity and emotion”.

Writing in The Wall Street Journal, William Meyers notes that because Maier used a medium-format Rolleiflex, rather than a 35mm camera, her pictures have more detail than those of most street photographers. He writes that her work brings to mind the photographs of Harry Callahan, Garry Winogrand, and Weegee, as well as Robert Frank.

As Sothebys’ and others are finally giving these female pioneers of photography Actually, her story is so interesting, she really needs a post all his own. I’m sure I’ll get to it later.

Ruth Bernhard

Ruth Bernhard moved to New York City in 1927. She worked as an assistant tat Delineator magazine. In 1935, she had a chance meeting with Edward Weston on the beach in Santa Monica.

By the late-1920s, while living in Manhattan, Bernhard was heavily involved in the lesbian sub-culture of the artistic community, becoming friends with photographer Berenice Abbott and her lover, critic Elizabeth McCausland. She wrote about her “bisexual escapades” in her memoir. In 1934 Bernhard began photographing women in the nude. It would be this art form for which she would eventually become best known.

Though many people were unaware of this, Bernhard produced the photography for the first catalog published by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The name of this exhibition was “The Art of The Machine.”

By 1944 she had met and became involved with artist and designer Eveline Phimister. The two moved in together, and remained together for the next ten years. They first moved to Carmel, California, where Bernhard worked with Group f/64. Soon, finding Carmel a difficult place in which to earn a living, they moved to Hollywood where she fashioned a career as a commercial photographer. In 1953, they moved to San Francisco.

All Genres

Most of Bernhard’s work is studio-based, ranging from simple still lifes to complex nudes. In the 1940s she worked with the conchologist Jean Schwengel. She worked almost exclusively in black-and-white, though there are rumours that she had done some color work as well. She also is known for her lesbian themed works, most notably Two Forms (1962). In that work, a black woman and a white woman who were real-life lovers are featured with their nude bodies pressed against one another.

A departure was a collaboration with Melvin Van Peebles (as “Melvin Van”), then a young cable car gripman (driver) in San Francisco. Van Peebles wrote the text and Bernhard took the unposed photographs for The Big Heart, a book about life on the cable cars.

In the early 1980s, Bernhard started to work with Carol Williams, owner of Photography West Gallery in Carmel, California. Bernhard told Williams that she knew there would be a book of her photography after her death, but hoped one could be published during her lifetime. Williams approached New York Graphics Society, and several other photographic book publishers, but was advised that “only Ansel Adams could sell black-and-white photography books.” Bernhard and Williams decided to sell five limited edition prints to raise the necessary funds to publish a superior quality of book of Ruth Bernhard nudes.

Adams Printer

The ensuing edition was produced by David Gray Gardner of Gardner Lithograph, (also the printer of Adams’s books) and was called The Eternal Body. It won Photography Book of the Year in 1986 from Friends of Photography. This book was often credited by Ruth Bernhard as being an immeasurable help to her future career and public recognition. The Eternal Body was reprinted by Chronicle Books and later as a deluxe limited Centennial Edition in celebration of Ruth Bernhard’s 100th birthday in October, 2005. Carol Williams credited Ruth Bernhard with encouraging her to venture into book publishing, and later published several other photographic monographs.

In 1984 Ruth worked with filmmaker Robert Burrill on her autobiographic film entitled, Illuminations: Ruth Bernhard, Photographer. The film premièred in 1989 at the Kabuki theater in San Francisco and on local PBS station KQED in 1991. Bernhard was inducted into the National Women’s Caucus for Art in 1981. She was hailed by Ansel Adams as “the greatest photographer of the nude”. Bernhard died in San Francisco at age 101.

Lisette Model

Lisette Model was born on November 10, 1901 in Austria, later emigrating to America. Model left for Paris after her father’s death in 1924 to study voice with Polish soprano Marya Freund. It was during this period that she met her future husband, the French-Jewish painter Evsa Model. In 1933, she gave up music and recommitted herself to studying visual art, at first taking up painting as a student of Andre Lhote, whose other students included Henri Cartier-Bresson and George Hoyningen-Huene. She also took up photography, taking basic instruction in darkroom techniques from her younger sister, who was a professional photographer.

Visiting her mother in Nice in 1934, Model took her camera out on the Promenade des Anglais and made a series of portraits, which are among her most widely reproduced and exhibited images. These close-cropped, often clandestine portraits of the local privileged class already bore what would become her signature style: close-up, unsentimental and unretouched expositions of vanity, insecurity and loneliness.

Model’s compositions and closeness to her subjects were achieved by enlarging and cropping her negatives in the darkroom.

She finally moved to NYC and worked as a photographer for PM magazine and regularly published in Harper’s Bazaar by editors Carmel Snow and Alexey Brodovitch. Model eventually became a member of the New York Photo League and studied with Sid Grossman until their demise in 1951. Model was an active League member and served as a judge in membership print competitions. In 1941, the League hosted her first solo exhibition. From 1941-1953, she was a freelance photographer and contributed to many publications including Harper’s Bazaar, Look, and Ladies’ Home Journal.

Model died in 1983 from heart and respiratory disease.

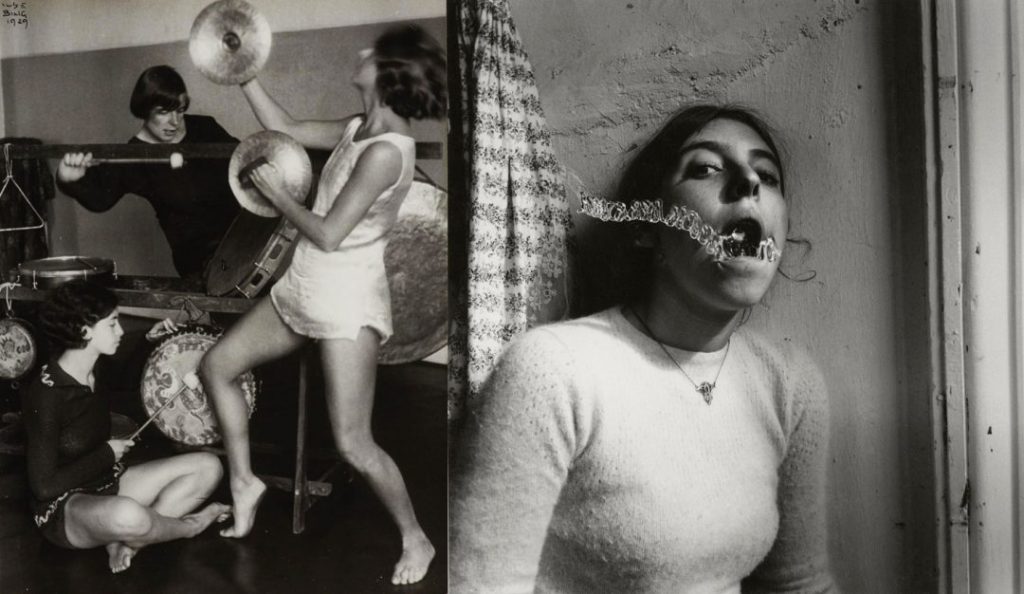

Ilse Bing

She was born in March 1899 and was a German avant-garde and commercial photographer who produced pioneering monochrome images during the inter-war era. Her move from Frankfurt to the burgeoning avant-garde and surrealist scene in Paris in 1930 marked the start of the most notable period of her career. She produced images in the fields of photojournalism, architectural photography, advertising and fashion, and her work was published in magazines such as Le Monde Illustre, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vogue. Respected for her use of daring perspectives, unconventional cropping, use of natural light, and geometries, she also discovered a type of solarisation for negatives independently of a similar process developed by the artist Man Ray.

Her rapid success as a photographer and her position as the only professional in Paris to use an advanced Leica camera earned her the title “Queen of the Leica” from the critic and photographer Emmanuel Sougez.

Museum of Modern Art

In 1936, her work was included in the first modern photography exhibition held at the Louvre, and in 1937 she traveled to New York where her images were included in the landmark exhibition “Photography 1839–1937” at the Museum of Modern Art.

She remained in Paris for ten years, but in 1940, when Paris was taken by the Germans during the World War II, she and her husband, both Jews were expelled and interned in separate camps in the South of France. Bing spent six weeks in a camp in Gurs, in the Pyrenees, before rejoining her husband in Marseille, where they waited for nine months for the US visas. They were finally able to leave for America in June 1941. There, she had to re-establish her reputation, and although she got steady work in portraiture, she failed to receive important commissions as in Paris.

By 1947, Bing came to the realization that New York had revitalized her art. Her style was very different; the softness that characterized her work in the 1930s gave way to hard forms and clear lines, with a sense of harshness and isolation. This was indicative of how Bing’s life and worldview had been changed by her move to New York and the war-related events of the 1940s.

She died in 1998 at the age of 99.

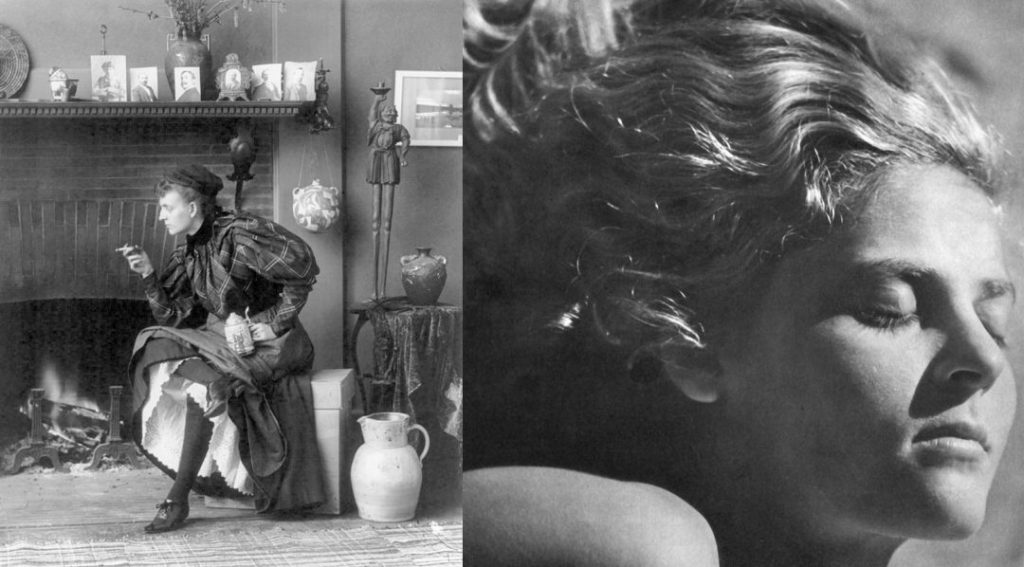

Frances Benjamin Johnston

Frances “Fannie” Benjamin Johnston was born in 1864 making her one of the earliest American female photographers and photojournalists. You could say all female photographers spring from her.

An independent and strong-willed young woman, she wrote articles for periodicals before finding her creative outlet through photography after she was given her first camera by George Eastman, a close friend of the family, and inventor of the new, lighter, Eastman Kodak cameras. She received training in photography and dark-room techniques from Thomas Smillie, director of photography at the Smithsonian.

She gained further practical experience in her craft by working for the newly formed Eastman Kodak company in Washington, D.C., forwarding film for development and advising customers when cameras needed repairs. In 1894 she opened her own photographic studio in Washington, D.C., on V Street between 13th and 14th Streets, and at the time was the only woman photographer in the city. She took portraits of many famous contemporaries including Susan B. Anthony, Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington. Well connected among elite society, she was commissioned by magazines to do “celebrity” portraits, such as Alice Roosevelt’s wedding portrait, and was dubbed the “Photographer to the American court.” She photographed Admiral Dewey on the deck of the USS Olympia, the Roosevelt children playing with their pet pony at the White House and the gardens of Edith Wharton’s famous villa near Paris.

Ladies’ Home Journal

The Ladies’ Home Journal published Johnston’s article “What a Woman Can Do With a Camera” in 1897 and she co-curated an exhibition of photographs by twenty-eight women photographers at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, which afterwards travelled to Saint Petersburg, Moscow, and Washington, DC. She traveled widely in her thirties, taking a wide range of documentary and artistic photographs of coal miners, iron workers, women in New England’s mills and sailors being tattooed on board ship as well as her society commissions. While in England she photographed the stage actress Mary Anderson.

In the 1920s she became increasingly interested in photographing architecture, motivated by a desire to document buildings and gardens which were falling into disrepair or about to be redeveloped and lost. Her photographs remain an important resource for modern architects, historians and conservationists. She exhibited a series of 247 photographs of Fredericksburg, Virginia, from the decaying mansions of the rich to the shacks of the poor, in 1928. The exhibition was entitled Pictorial Survey–Old Fredericksburg, Virginia–Old Falmouth and Nearby Places and described as “A Series of Photographic Studies of the Architecture of the Region Dating by Tradition from Colonial Times to Circa 1830” as “An Historical Record and to Preserve Something of the Atmosphere of An Old Virginia Town.”

American Institute of Architects

Johnston was named an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects for her work in preserving old and endangered buildings and her collections have been purchased by institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Baltimore Museum of Art. Although her relentless traveling was curtailed by petrol rationing in the Second World War the tireless Johnston continued to photograph. Johnston acquired a home in the French Quarter of New Orleans in 1940, retiring there in 1945, where she died in 1952 at the age of 88.

Dora Maar

Dora Maar was born in 1907, was a photographer of French and Croatian descent. She is actually more famous as Pablo Picasso’s muse of nearly a decade (beginning late 1930s), including for his widely known pieces Guernica and The Weeping Woman. Maar painted some minor elements of Guernica, but she became better known in the art world via her photographs of the stages of Picasso’s execution of the masterwork in his rue des Grands Augustins workshop. Heading to Paris, she trained at school for photography and thereafter entered the Académie Julian, which was known to offer women “the same training as male students at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts”. During and immediately following her training, Dora Maar spent time on both photography and painting, with an eventual emphasis on photography leading to its full-time pursuit.

She died in France in 1997.

Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems was born in 1953. She is an African American artist who works with text, fabric, audio, digital images, and installation video but is best known for her work in the field of photography. Her award-winning photographs, films, and videos have been displayed in over 50 exhibitions in the United States and abroad and focus on serious issues that face African Americans today, such as racism, gender relations, politics, and personal identity. She has said, “Let me say that my primary concern in art, as in politics, is with the status and place of Afro-Americans in our country.” More recently however, she expressed that “Black experience is not really the main point; rather, complex, dimensional, human experience and social inclusion … is the real point.”

The first comprehensive retrospective of her work opened in September 2012 at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tennessee, as a part of the center’s exhibition Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video. Curated by Katie Delmez, the exhibition ran until January 13, 2013 and later traveled to Portland Art Museum, Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Cantor Center for Visual Arts. The 30-year retrospective exhibition opened in January 2014 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. Weems’ work returned to the Frist in October 2013 as a part of the center’s 30 Americans gallery, alongside black artists ranging from Jean-Michel Basquiat to Kehinde Wiley.

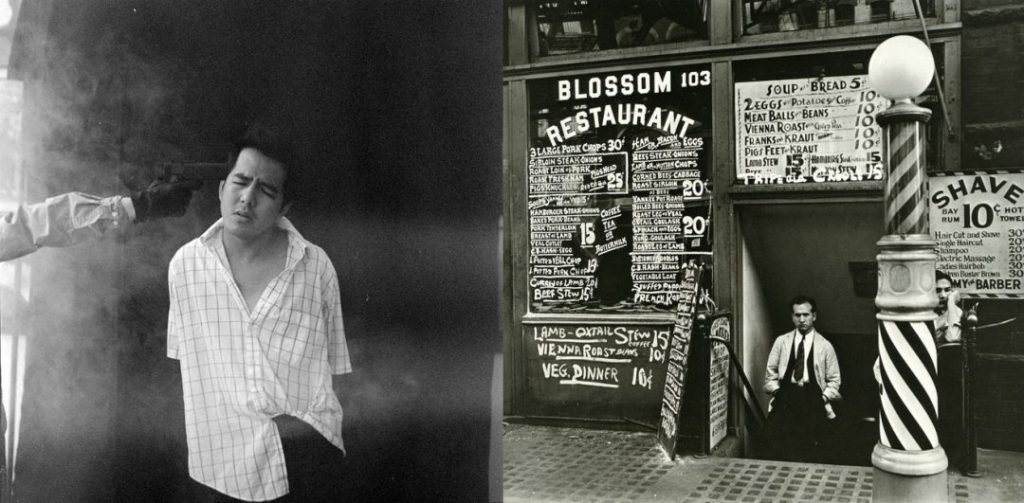

Berenice Abbott

Berenice Abbott was born July 17, 1898 and was an American photographer best known for her black-and-white photography of New York City architecture and urban design in the 30’s.

In early 1929, Abbott visited New York City, ostensibly to find an American publisher for Atget’s photographs. Upon seeing the city again, however, Abbott immediately saw its photographic potential. Accordingly, she went back to Paris, closed up her studio, and returned to New York in September. Her first photographs of the city were taken with a hand-held Kurt-Bentzin camera, but soon she acquired a Century Universal camera which produced 8 x 10 inch negatives. Using this large format camera, Abbott photographed New York City with the diligence and attention to detail she had so admired in Eugène Atget. Her work has provided a historical chronicle of many now-destroyed buildings and neighborhoods of Manhattan.

Abbot and the Museum of the City of NY

Abbott worked on her New York project independently for six years, unable to get financial support from organizations, foundations, or individuals. She supported herself with commercial work and teaching at the New School of Social Research beginning in 1933. In 1935, however, Abbott was hired by the Federal Art Project as a project supervisor for her “Changing New York” project. She continued to take the photographs of the city, but she had assistants to help her both in the field and in the office.

This arrangement allowed Abbott to devote all her time to producing, printing, and exhibiting her photographs. By the time she resigned from the FAP in 1939, she had produced 305 photographs that were then deposited at the Museum of the City of New York. Abbott’s project was primarily a sociological study embedded within modernist aesthetic practices. She sought to create a broadly inclusive collection of photographs that together suggest a vital interaction between three aspects of urban life: the diverse people of the city; the places they live, work and play; and their daily activities. It was intended to empower people by making them realize that their environment was a consequence of their collective behavior.

In 1935, Abbott moved into a Greenwich Village loft with the art critic Elizabeth McCausland, with whom she lived until McCausland’s death in 1965. McCausland was an ardent supporter of Abbott, writing several articles for the Springfield Daily Republican, as well as for Trend and New Masses . In addition, McCausland contributed the captions for the book of Abbott’s photographs entitled Changing New York which was published in 1939. In 1949, her photography book Greenwich Village Today and Yesterday was published by Harper & Brothers.

She died in 1991.

Helen Levitt

The late New York-based photographer Helen Levitt, born in 1913, is known for her stirring take on street photography, first in black and white and later in gripping color. Under the patronage of a Guggenheim grant in the late 1950s and early 1960s, she captured hundreds of color negatives of New York City that were tragically stolen by a burglar a decade later. Thankfully, she continued to take photographs up until her death in 2009, many of which are memorialized in a book of her work titled Here and There. She is probably one of the most well known photographers’ here, along with Berenice Abbott. I’ve shortened her bio because she is actually fairly well known.

She died in 2009.

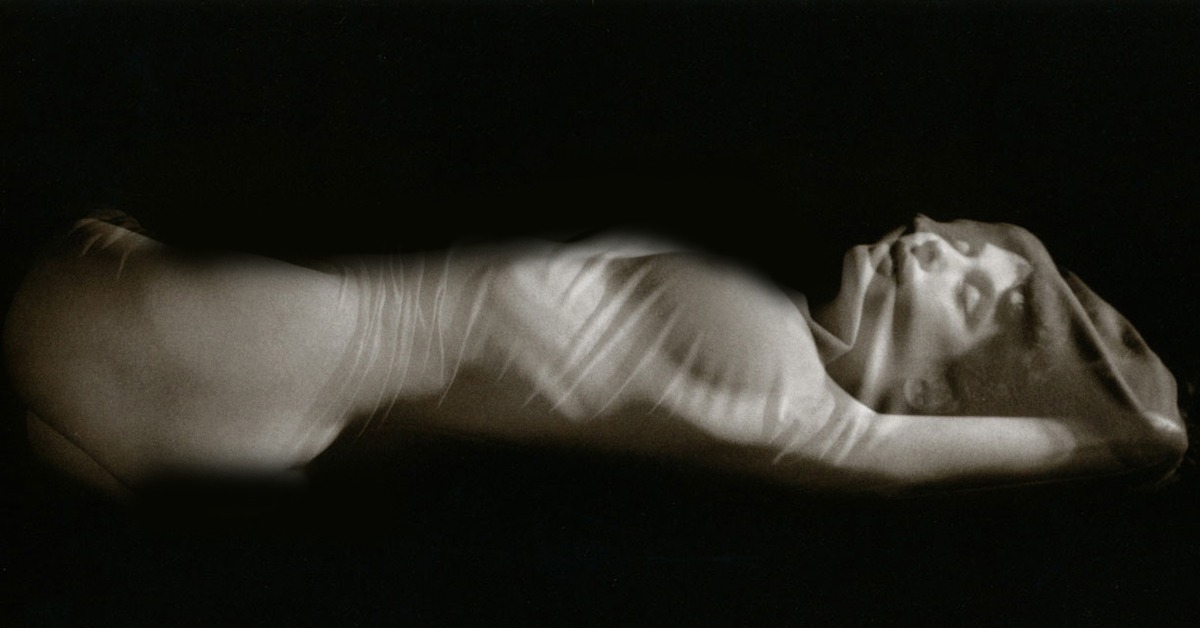

Francesca Woodman

Born in 1958 in Colorado, Francesca Woodman tended to depict nude women in her photographs, many of whom were captured in ethereal poses and settings. She was prone to putting herself in front of her camera, positioned in sparse domestic settings that made her body take on a ghostly presence. As many critics have noted, Woodman seemed to have a particular talent in using photography to play with the ways we perceive time.

“Unlike the photographs we take of ourselves today … time itself went into Francesca Woodman’s pictures.“The ‘timeless time,’ to borrow a phrase from her contemporary Nico, inside Woodman’s photographs, was the time it took to select the elements for their semi-improvisatory making, plus the time it took to take them, behind which was, of course, each contour of every single thing she ever saw or did in her life, as is true for all artists.”

And so we have just some of the female pioneers of photography,…some known, some not, but all contributors in their unique way.

What’s weird is that they all used a Rollei TLR at one time or another. You would think a Leica would be more “ladylike”. Guess I’m just a sexist. Find Rollei TLR